“Heart Failure Self Management Project”

A Case Study using Ethnographically-Prepared Patient Materials

Department of Veterans Affairs, VISN 11, Ann Arbor VA Medical Center,

Ann Herm, RN MS CNAA; Shirley Grey, RN MSN; Nancy M. Valentine, RN PhD MPH FAAN FNAP; Craig M. Olson, PhD; and Leonard C. Rogers

ABSTRACT

Self management of heart failure (HF) requires patients to adopt lifestyle changes as well as to recognize and respond to symptoms. Interventions intended to reduce rates of utilization often involve high levels of professional labor to assist patients in these activities and low levels of investment in developing tools for independent patient success. For example, recent ethnographic research at Kaiser Permanente, aimed at improving post discharge outcomes, appears to have applied its insights primarily to increasing referrals to professional services (Neuwirth, 2010). The Veterans Administration Medical Center at Ann Arbor, Michigan wished to test whether ethnography could be applied instead to tools enhancing patients’ independent self management. Such a program would involve a low level of nursing resources and a high level of materials standardization.

This case study is a first attempt to tease apart the effect of the labor component from that of materials in a program to promote successful HF self care. In cost-constrained environment with limited human resources, it is appropriate to explore increasing the effectiveness of materials rather than continuing to increase skilled labor.

The measure of effectiveness was whether readmission rates and average length of stay (ALOS) on readmission would be lower for patients receiving materials derived from ethnographic research. The VA Medical Center located such materials already developed, the HF SelfCareKit1 from Communication Science, Inc. Estimating cost savings, surveying nurse satisfaction and eliciting patient response to the materials were also important to the VA.

RESULTS

Over 90 days, 58.2% of the Control Group (N=67) were readmitted vs. 35.5% of patients receiving the HF SelfCareKit (N=31), an improvement of 39% (p.<.05). Readmissions dropped at both 31 and 61 days post discharge; however, group sizes at these points were too small for statistical significance. ALOS on readmission also showed a small improvement which might be significant if adjusted for the greater acuity of the Treatment Group. Net savings from reduced readmissions in 90-days was estimated at $184,579. Nurses were very satisfied; by unanimous agreement (100%), they would like the SelfCareKit available permanently. Patients reported adopting new behaviors such as organizing medication (68%), weighing daily (52%) and keeping a diary (36%).

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the investigation suggest that ethnographically-developed selfcare materials reduce readmission rates and ALOS of HF patients with no additional intervention from staff. The Ann Arbor VA recommends a larger, more rigorously-designed study compare return on investment: Net savings through distributing SelfCareKits versus the net of other methods of discharge preparation.

1At the time of the IRB approval and execution of the case study, the SelfCareKit was also known by the name “Careguide.” That trademark has since been sold to a different company and thus could be misleading to a reader seeking further information. For this reason, the name is not used in this report.

CASE STUDY REPORT

BACKGROUND

HF leads to frequent and costly admissions (Yehle, 2009). Patients involved in self-care have fewer admissions. (Eastwood, et.al, 2007; Yehle, 2009) Patients active in their care report a better quality of life. (Bushnell, 1992; Sulzbach-Hoke, Kagan, Craig, 1997; Cline, Bjorck-Linne, Israelsson, Willenheimer, Erhardt, 1999; Ni, Nauman, Burgess, Wise, Crispell & Herschberger, 1999; Krumholz, Amatruda & Smith, 2002). Evidence for enhancing self-care to reduce costs is so strong that the Specification Manual for National Hospital Quality Measures from The Joint Commission requires hospitals document delivery of written instructions to HF patients (2008).

Despite this mandate, no standard exists for judging instructions to be understandable, engaging or complete. Inevitably some instruction is inappropriate or inadequate: Patients may perceive condescension or writers’ assumptions may cause critical omissions. Kaiser ethnography identified gaps in patient knowledge that surprised clinicians. Kaiser chose to fill the gaps primarily with referrals to professionals (Neuwirth, 2010). To date, most attempts to enhance self care have been labor-intensive. All nine CMS demonstrations used teaching, case management and coaching (McCall, Cromwell, Urato, Rabiner, 2008; Clinical Trials.gov 2008). Whether they worked is at best uncertain (McCall, 2008). Regardless of benefit, labor-based solutions may be too costly.

No CMS demonstration pursued new methods to develop materials. The VA wished to examine whether gaps in patients’ knowledge and engagement could be filled with ethnographically-designed material. The commercially-available SelfCareKit reflects current guidelines for HF management from the Heart Failure Society of America and the American Heart Association, et.al. (Paul, 2008). Its uniqueness is not in clinical content but in the way ethnographic insight leads to sociolinguistic restructuring of content. Insight came from ethnographers travelling to 300 locations to observe patients at home, work and in the community. Researchers videotaped and debriefed. Analysis revealed gaps across socioeconomic groups; e.g., nearly all patients lacked a framework to see how seemingly diverse elements of self care fit into a coherent program. SelfCareKit instructions reflect the patients’ own language and avoid terms commonly used by clinicians that tend to trigger resistance.

PURPOSE

The VA case study examines whether HF readmission rates are lower for patients receiving materials developed by ethnographic research prior to writing instructions or designing tools. The Medical Center located such materials already developed, the Heart Failure SelfCareKit from Communication Science, Inc. If the kit was effective, cost savings would be estimated. Secondary aims of this study were to elicit patient response to the materials and to determine nurse satisfaction with incorporating the distribution of the kit into their work.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Certainly some labor-intensive programs have had success. In a study of 197 patients, the treatment group received six weekly clinic visits with counseling, six weekly primary care visits with education and a diary. The control received nothing—and scored higher risk of readmission. (Eastwood, 2007). Other programs use technology—the labor is the clinicians’ surveillance and response. Chaudhry (2007) used electronics on 134 HF patients for 18 months. Nurses contacted physicians when readings went out of range. This case study will not challenge those results, but explore whether comparable results can be achieved with less professional labor.

In consumer industries, the end user must be engaged by communications and product design alone.To succeed, Ethnography is standard. In contrast to focus groups, ethnography is one-on-one observation in the user’s space. Focus groups are often more about the dynamics of the group and its leader than about a true user experience. “We see people’s behavior on their terms, not ours,” declares Ken Anderson, head of ethnography at Intel (HBR, 2009). Ethnography is used in health care to redesign devices for professionals (Wilcox, 2003), improve doctor-patient interviews (The, 2000) or bridge cultures (Fleming, 2009). For the SelfCareKit, ethnography revealed patients’ desire to see actions connect to outcomes. Thus SelfCareKit diaries have a unique layout to allow spotting at a glance relationships between actions and monitor readings. Patients also wanted to laugh, but their providers had tended to indulge in “humor” patients did not find funny. SelfCareKits reflect the end users’ humor.

Sociolinguistics is a staple of consumer copywriting for effective, brief communication. Sociolinguistics overlaps ethnography to study how different social groups, such as patients and providers, use different language for the same content (Gumpertz, 2008). The differences can be dramatic: At Rush Medical Center, 70% of nurses were satisfied with materials for discharge post surgery. However, when they called patients one week after discharge, they found 96% of 86 patients discharged over three months could not follow the instructions. Rush then adopted SelfCareKits. Sociolinguistics did not change clinical content; it changed the language. When Rush called another three-month set of patients (N=68) one week after discharge, 92% reported they could follow the instructions. (Hospital Peer Review Journal, 2001). In the SelfCareKit, sociolinguistics guides the use of extended metaphor and story-telling. It also structures goals as the major organizational headings rather than topics.

In summary, the literature shows self care achieves better outcomes. However, studies seem to assume the need for professional labor; most do not test (as Rush did) whether material can stand on its own. This case study is a first attempt to tease apart the effect of materials alone on successful self care for HF.

SETTING

VISIN 11 Veterans Administration Medical Center is a 100-bed hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The study was conducted on an inpatient cardiac care telemetry unit.

METHODS

The VA Internal Review Board, Subcommittee on Human Studies, approved the project. Confidentiality was maintained per the Human Participants Protection Policy. Data were maintained in a locked cabinet and secure data base. Results were tabulated at 31, 61 and 90 days.

SUBJECTS

Researchers chose a historical control group to compare with a convenience sample of 50 from the telemetry unit. For the Control, the VA Quality Department identified 264 candidates by data extraction, 2006-2007. Sixty-seven met the criteria of being discharged to home with a primary diagnosis of HF on the initial admission. Of the fifty candidates for the Treatment Group, thirty one (31) qualified. The case study did not balance demographics (gender, age, NY HF Class), as a larger study would. Instead, all subjects meeting the criteria were included:

- HF discharge diagnosis on initial admit, documented by a provider in the medical record

- Discharged to home, with or without homecare

- Less than 420 pounds (limit of the scale in the kit) and over 18 years of age

- Able to read English at least at a fourth-grade level (the reading level of the kit text)

Subjects were excluded if they were Class IV CHF according to the NY Heart Association Classification, discharged to a site other than home, wheel chair bound or unable to provide written informed consent.

PROTOCOL

Preparation

Nurses from all shifts received a 20-minute orientation to ethnography, the study objectives and the kit components. Kit contents were available on line for detailed examination.

Enrollment & Delivery

The Unit Charge Nurse, nursing and medical staff identified potential enrollees among those admitted to 5 West during the study period: A history of HF, likely to be discharged with a HF diagnosis. Thirty-one patients met the criteria and agreed to participate. After enrollment, the nursing staff was notified by a note on the patient’s chart. The Study Coordinator supervised the enrollment and the distribution of SelfCareKits. A nurse oriented the patient and family to kit immediately after enrollment. As soon as the patient could stand, the nurse had the patient use the items in the kit to practice self-care tasks. Before discharge, the nurse instructed the patient to contact the hospital if the patient (1) gained two or more pounds in two days or (2) had difficulty breathing. For the study goal, to test materials without professional support, no staff would contact the patient after discharge.

Data Collection

Primary Outcome Measures. Chart review yielded ALOS on initial admission and readmissions at 31, 61 and 90 days. Data on ALOS on readmission were retrieved by electronic data extraction. Cost savings are reported on actual savings compared to the Control.

Secondary Outcome Measures. For thepatient, a printed survey was in the kit with a stamped envelope, to be returned four weeks after discharge, reporting changes in behavior, perceptions of the kit and level of confidence in self care. If a patient did not return the survey, a staff member called. For the nursing report, an electronic survey went to staff halfway through the study and again at the end of the period, asking how the kits impacted work flow, perceptions of the kit and level of satisfaction.

RESULTS

Primary Measures: Readmission Rates, Length of Stay on Readmission, Cost Savings

Total Readmissions: The Control Group had 67 members, of which 39 had at least one readmission, or 58.2%. The Treatment Group had 31 members. Eleven had at least one readmission, 35.5%. The improvement was 39%, at a confidence level of 95% that the improvement was due to the intervention.

Table 1 Control and Treatment Group Outcomes

| Sample | Number | Number with at least one readmission | p |

| Control | 67 | 39 | 0.582090 |

| Treatment | 31 | 11 | 0.354839 |

| Difference = p (1) – p (2) = .227251 (22.7%) 95% Confidence Interval for the difference [0.215429, 0.432959] Test for difference = 0 vs. not=0: 2.17 P-value = 0.030 Fisher’s exact test: P-Value = 0.050 |

Subgroup Readmissions: All 67 of the Control Group and all 31 of the Treatment Group had HF as the primary diagnosis on their initial admission. Readmissions, however, could have HF as either primary or secondary diagnosis, yielding complex combinations for subgroups. Although all Treatment subgroups performed better than the Control subgroups, none was large enough for statistical significance.

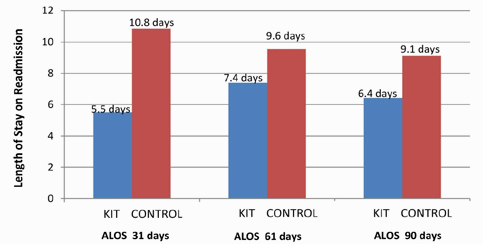

Length of Stay: The Treatment Group included an outlier whose initial admission was 47 days and readmission lasted 16 days. Without the outlier, the Treatment Group still had a higher ALOS on the initial admission, 7.5 versus 6.33, suggesting that the Treatment Group—even without the outlier—may have been sicker than the Control. With the outlier, the Treatment Group was certainly sicker. Despite this greater severity, members of the Treatment Group (not including the outlier) who were readmitted needed slightly less time to recover than their counterparts in the Control Group, 5.8 days vs. 6 days.

Table 2 ALOS for Control and Treatment Groups

| Group | Length of Stay on Initial Admission | Length of Stay on Readmission |

| Control Group |

6.33 |

6.00 |

| Treatment Group with Outlier |

11.09 |

6.73 |

| Treatment Group without Outlier |

7.5 |

5.80 |

Alternatively, the outlier may be eliminated by considering only patients with HF as a primary diagnosis on both admissions. The first LOS for this Control subgroup was 5.82 days. The Treatment subgroup was 8.28 days. This strengthens the suggestion that the Treatment Group was sicker. If true, the kit may have been even more effective: LOS on readmission was 7.71 days for the Control and 7.00 days for the Treatment Group. A difference in LOS is still visible when the population is divided by time period, but statistical analysis is clouded by the small numbers in each group and the lack of an algorithm to adjust for severity.

Figure 1. Length of Stay on Readmission for All Patients,

HF as Primary or Secondary Diagnosis

Cumulative Average at 31, 61 and 90 days Post Discharge

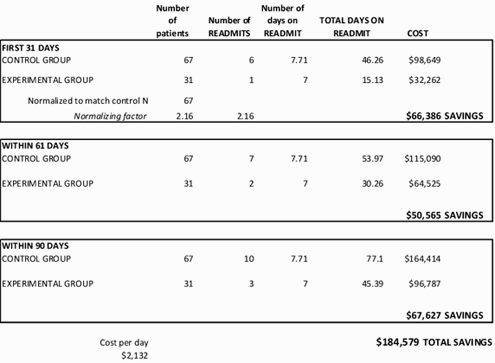

Cost savings are estimated by comparing Control costs to Treatment Group costs. Data was normalized to the Control N (31 X 2.16 =67). In a minor attempt to adjust for severity, only those patients with a primary diagnosis of Heart Failure on both admissions were considered. VAMC average cost per day for HF, April 2006-March 2007, was $2,132.48. The difference between the two Groups in 31 days was $66,386. A HF SelfCareKit is $120, or $8040 for 67 patients. Net savings are $58,346, or $870 per patient—an ROI of 7.26. Savings are constant for other periods because of shorter LOS.

Table 3 Cost Analysis of Readmissions between Control and Treatment Groups

with Heart Failure as Primary Diagnosis on Both Initial Admission and Readmissions

SECONDARY MEASURES: Patient Self-Reported Change and Staff Satisfaction

Patient Response: The pill organizer was the most popular item: 68% reported using it. The kit changed 63% of the patients’ diets. Of those who reported no food changes, 38% believed their current diet was correct. Fifty-two percent did not weigh themselves before the kit but began to weigh in at least once a week after. One fourth of the patients were already tracking symptoms before receiving the kit. But a larger number, 36%, adopted the SelfCareKit journal and 43% took it to their provider. Exercise increased for 21%.

Staff Response: By unanimous agreement (100%), nurses would like to use SelfCareKits permanently. They agreed the kits were more convenient than locating supplies and instruction pages and organizing them for the patient at discharge. Fifty percent judged no further instruction was needed beyond the kit.

DISCUSSION

Why would ethnography make materials more effective? Isn’t adjusting for “health literacy” adequate? Health literacy takes clinical text and adjusts for comprehension. Ethnography and sociolinguistics structure the content to match the thought patterns of the user (Goffman, 1974), aiming not just for comprehension but engagement and long term commitment. These claims are worth investigating in a larger study, since the prospect of lower costs from decreasing the need for professional labor is compelling.

LIMITATIONS

The sample size was small. Limiting the pool of candidates to one floor prevented a larger sample size. A larger study could use more locations for recruitment while maintaining the requirement that the initial admission diagnosis be HF. Some candidates may have been missed simply from workplace distractions.

The Control Group was historical rather than concurrent. A truly rigorous study could randomize incoming patients to a treatment and control group in order to eliminate any variables inherent in a historical control.

Whether patients returned to another facility was not investigated. A study with concurrent groups could contact patients at 31, 61 and 90 days to ask if there had been a readmission and if so, for what reason.

The sample included only men and did not adjust for severity. A larger study could plan to balance gender and prepare for differences in age and acuity.

CONCLUSIONS/RECOMMENDATIONS

The results from this case study are sufficiently positive to warrant further study. A new study should expand the number of locations for subject recruitment to ensure a sufficiently large N for statistical significance. A study manager should supervise at least the first few weeks of the study to ensure that the enrollment process is properly executed. The demographics of enrollees should be noted. It may be more effective to run the program at the clinic level, catching patients earlier in their disease process and measuring reductions in admissions averted as well as readmissions prevented. In any study, acuity levels should be addressed in the analysis.

Study groups should be concurrent and returns to other facilities investigated. Most of all, a new study should emphasize the financial impact of ethnographically-designed materials: Not only analyzing readmission ALOS costs, but also comparing workflow productivity and cost of distributing selfcare kits versus the costs other methods of discharge preparation—particularly those requiring high levels of professional labor.

REFERENCES

Anderson K. Ethnography: Key to Strategy Harvard Business Review (March 1 2009), online edition retrieved Jan 2, 2011 at http://hbr.org/2009/03/ethnographic-research-a-key-to-strategy/ar/1.

Bushnell F. (1992). Self-care teaching for congestive heart failure patients. J of Gerontological Nursing, 18, 27-32.

Chaudhry S, Wang Y, Concato J Gill G, Krumholz H. (2007). Patterns of weight change preceding hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation, 116(14), 1526-29.

Cline C, Bjorck-Linne, Israelsson B, Willenheimer R, Erhardt L, (1999). Non-compliance and knowledge of prescribed medication in elderly patients with heart failure. European J of Heart Failure, 1, 145-9.

Eastwood C, Travis L, Morgenstern T & Donaho E.(2007). Weight and symptom diary for self-monitoring in heart failure clinic patients. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 22(5), 382-89.

Fleming, J., Mahoney, J., Carlson, E., & Engebretson, J. (2009). An ethnographic approach to interpreting a mental illness photovoice exhibit. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 23(1), 16-24.

Goffman E, (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. London: Harper and Row.

Gumperz J and Cook-Gumperz, J. Studying language, culture, and society: Sociolinguistics or linguistic anthropology? Journal of Sociolinguistics 12(4), 2008: 532–545.

Hospital Peer Review Journal(2000) Discharge kit boost patient satisfaction 285%. September 2000, 121-122.

The Joint Commission. (2005). Specification manual for national hospital quality measures. Retrieved January 8, 2008 http://www.jacaho.org/pms/core+measures/aligned_manual.htm

Krumholz H, Amatruda J & Smith G et al., (2002). Randomised trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. Journal of American College of Cardiology, 39, 83-89.

McCall N, Cromwell J, Urato C, Rabiner D, (2008). Evaluation of phase I of the medicare health support pilot program under traditional fee-for-service medicare: 18-month interim analysis. Report to Congress 9

Neuwirth E, Price P & Bellows J. Video Ethnography ToolKit: Motivating Quality Improvement (2010). Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute, accessed Jan 2, 2011 at http://kpcmi.org/news/ethnography/index.html

Ni H, Nauman D, Burgess D, Wise K, Crispell K & Herschberger R. (1999). Factors influencing knowledge of and adherence to self care among patients with heart failure. Archives of internal Medicine, 159, 1613-19.

Paul S. (2008). Hospital discharge education for patients with heart failure: What really works and what is the evidence? Critical Care Nurse, 28, 2, 66-82.

Sulzbach-Hoke L, Kagan S & Craig. (1997). Weighing behavior and symptom distress of clinic patients with CHF Med-Surg Nursing, 6m 288-93

The AM, Hak T & Wal G. (2000) Collusion in doctor patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study, British Medical Journal 321:1376-81.

Wilcox S. (2003). Applying universal design to medical devices. Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry, Jan 2003.

Yehle K, Sands L, Rhyders P & Newton G. (2009). The effect of shared medical visits on knowledge and self-care in patients with heart failure: A pilot study. Heart & Lung. 38(1), 25-33.